New York Times Article - Sandra Kazan Speech Coach

Learning to Escape A Prison of Silence

In a world gone wicked, silence equaled life.

Surrounded by the barbed wire and routinized evil of places like the Bergen-Belsen concentration camp, Helga Newmark learned that the road to survival was best traveled silently and anonymously, so she endured three years of captivity by quietly blending into the background, like some obedient, respectful child. Decades later as an adult, her breathy voice -- sometimes barely audible -- was a reminder that the skill that once saved her later hemmed her in emotionally.

"I pretty much shut out the world," said Mrs. Newmark, who is 61 years old. "The world out there was dangerous. For a very long time I lived behind my own barbed-wire fence."

Decades after doubting the divine, she found her calling and enrolled in rabbinical school. There she found her voice -- during the last year at Hebrew Union College in Greenwich Village she has worked with a speech coach who has slowly helped ease her and her story into the open.

'A Great Deal to Say'

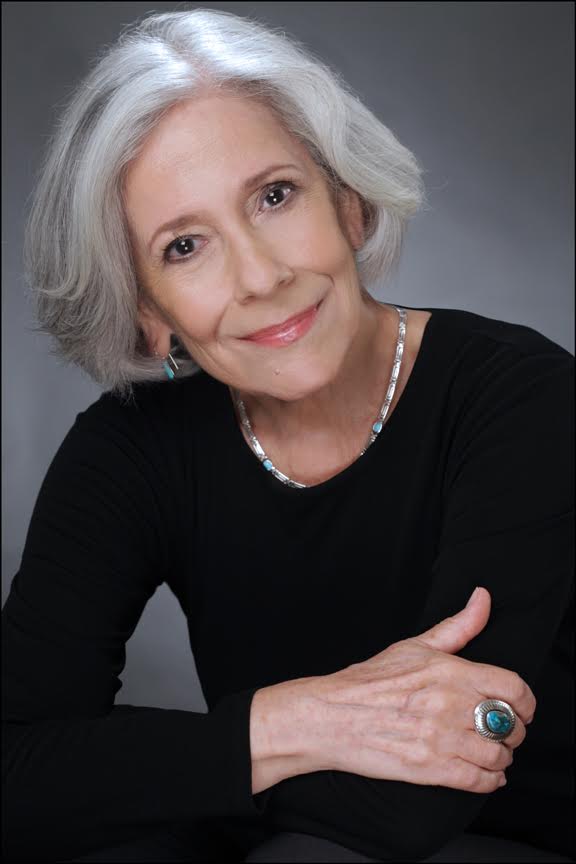

"She has a great deal to say," said her teacher, Sandra Kazan. "And now she can finally be heard."

Mrs. Newmark's journey of faith -- in herself, her world and her God -- began in Germany, where she was born into an Orthodox Jewish family in 1932. The next year her father, a jewelry manufacturer, moved them to the Netherlands.

When World War II broke out, she and four relatives were imprisoned in a series of concentration camps. She learned to stay low, be quiet and live.

"I survived because I tried not to be noticed," she said. "I was inconspicuous."

Others turned to prayer and faith as they tried to glean the slightest hint of the divine plan, but not Mrs. Newmark, who said her family was not particularly observant.

"I never gave God a thought," she said. "I think it helped a lot of people in camp to have faith and find a meaning, but I didn't come from that place."

When the war ended, she emerged with her mother, and little else.

"I came out of the camps hearing my mother say there is no God," Mrs. Newmark said. "For a long time, until I had my first child, I did not entertain the thought of God."

But the thoughts soon came. Other Religions.

Married and living in New Jersey in the 1950's, she explored other religions, reading and talking about Catholicism and Buddhism. But the Eastern tradition was too alien, as was the Christian concept that Jesus Christ was fully God and man.

She embraced her Jewish roots, and soon a young rabbi convinced her to teach Sunday school. Within years, she became the principal of a religious school in New Jersey. To bolster her knowledge, she returned to school herself, studying Hebrew at the Jewish Theological Seminary in Manhattan. There, she discovered the pull of such rituals as the lighting of candles and the preparation of special meals on Friday evenings.

"I realized that there is a richness in our tradition, which I saw for the first time," she said. "It gave a structure to my life which had been missing."

The idea of becoming a rabbi grew slowly over time, held back by other traditions -- the idea that women of her generation got married, had children and little else. But once her three children were grown, she approached her rabbi about applying to Hebrew Union College, a school that trains rabbis for the Reform movement.

Five-Year Program

Rejected the first time around, she instead went to Yeshiva University in Manhattan and studied for a master's degree in social work. Then she reapplied and was accepted into the five-year program.

"I think they had questions about my age and reflected a society that felt people over 50 really cannot learn the way a younger person might," she said.

Her classes in the three years she has been at the school include Bible studies, Hebrew, philosophy and liturgy. She admits she is a not a star student; her favorite course on the Talmud is also the one she finds most difficult.

"I like the fact that the rabbis in the Talmud deeply cared about what was happening in the world and really went into details, incredible details giving all sorts of examples," she said. "I'm terrible at following their thinking, I'm not good at logical thinking. But it's fascinating stuff."

Perhaps the most challenging course for student and teacher was the speech class required of all students as their preparation for delivering a sermon. Ms. Kazan, an actress who has taught the course for a decade, said Mrs. Newmark started the class with a monotonous, close-mouthed manner.

"She spoke in an exceptionally soft, breathy voice that could barely be heard," Ms. Kazan recalled. "Her articulation was less than adequate."

'Freeing the Self'

To free up her students, Ms. Kazan tries a variety of approaches: to encourage them to open their mouths while speaking, she has them read with their fists in their mouths; she also has them read fables and assume the voices of different characters; she even has them read while skipping around the room.

The voice, said Ms. Kazan, is connected to the body and the spirit. "We have to work on freeing the voice and freeing the self," she said. "Once they do it, they really are on the way to freeing themselves in front of an audience."

Mrs. Newmark has come a long way during the semester -- her voice is lively and expressive, strong and free enough to be easily heard in a group. A few weeks ago she made a presentation at an interfaith awards ceremony, and her friends commented on how she sounded different, better.

"She did things that were difficult for her to do," Ms. Kazan said. "But she was always willing to be challenged and take a risk."

Next Challenge

Mrs. Newmark's next challenge will come in two years, when she graduates and goes in search of a congregation. She does not think she would be a very academic rabbi, but she knows she has other strengths not learned in any classroom.

"I know what it's like to mourn and grieve," she said. "I know what it feels like to be in the prison of the self and to overcome those things -- to come out slowly and begin to trust again."

Read the article here.